On the surface listening seems to be a fairly straightforward skill, simply involving letting the other person talk and hearing what they have to say. But true listening, involving sustained attention and genuine interest is quite rare.

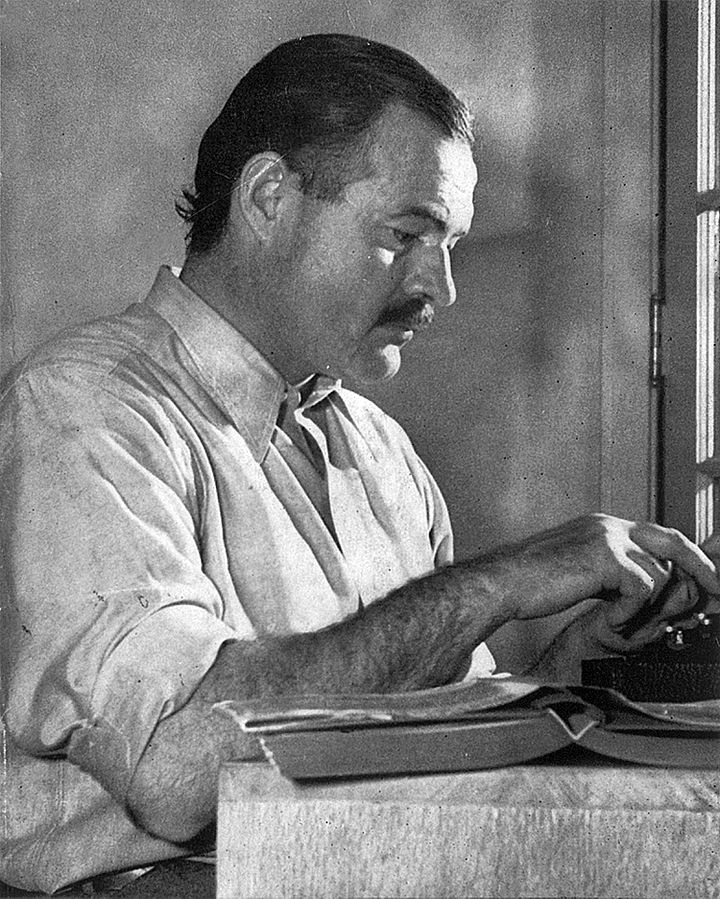

“When people talk, listen completely. Most people never listen” – Ernest Hemingway

In training, we like to emphasise that:

Listening is the most important skill in peer support

This is because the person doing the talking is being heard, which is therapeutic in itself, and also because those who are listening properly will understand and appreciate their perspective, and will be more able to help. This goes to the heart of what peer support is.

Listen to some peer supporters’ views on the importance of listening here:

In psychological terms, this kind of genuine listening is called ‘active listening’.

How to actively listen

It is useful to think of three aspects to active listening:

1) The actual content of what is being said

2) The person’s point of view (i.e. where they are coming from)

3) Their feelings about what they are saying

In other words, listen for content, perspective, and emotions.

Remember that you can also ‘listen’ to a person’s body language to gauge these three aspects of communication.

Here are seven ways in which you can take to listen actively:

1) Behaviour and body language

You may get some clues about what the person is saying or feeling by their body language. You also need to be aware of your body language. By displaying relaxed body language you may help the speaker to relax. The best way to control body language is to be aware of it.

List of things to consider:

- Eye contact

- Eyebrows

- Smiling

- Avoiding movement during a sitting interaction

- Hands – comfortably placed, but arms not crossed

- Both feet on the floor pointing in the same direction, uncrossed legs and ankles

- Face in their direction, but not directly, try to place both chairs at an angle

- Do not wriggle or jerk around.

- One suggestion is to look natural, which means to not think about this list!!!

2) Minimal encouragers

Use eye contact, open body language, a nod of encouragement or a few a few mmm’s or uh-huhs to show you are listening.

3) Silence is golden

Allow the peer to talk, and try not to fill all silences. It is alright if you are both silent for a while, and it allows time to think about what has been said.

4) “I” statements

Summarising what you think the peer said allows you to confirm that you have understood correctly, and allows the peer to correct you if you have misunderstood what they said. This does not mean that you are agreeing with what’s been said, just stating what you think has been said.

At first give yourself 5-10 seconds before making a response to think about:

- What the peer has said

- What brought on this feeling

Try to put into words how you think the peer might be feeling. Here are some examples:

It seems you feel ………

Is it possible you feel ………

I’m wondering if you feel ………

I get the impression you feel ………

Could it be that you feel ………

I’m sensing you feel ………

For example:

Facilitator: “I’m sensing you’re feeling angry because the doctor said you need insulin”

Peer: “No, I am feeling angry because I think I could have done something to prevent needing to go onto insulin”

5) Speaker’s frame of reference

Consider the speaker’s background, both cultural and personal, and be sensitive towards this. For example, someone might have smoked their whole life and it is the norm amongst those they work and socialise with. It is better to be aware of and work with this than making a snap judgement that they are in some way morally inferior!

6) Your opinions/emotions

Related to the last point, be aware of how your personal opinions and emotions might get in the way of support. It is natural that we draw on our opinions and emotions during conversation, but it would be unfortunate if they got in the way of helping someone.

7) Distractions

Try to overcome/avoid any distractions. This might include interruptions, noisy or uncomfortable rooms, visual distractions. It will also be distracting if you cannot hear the person properly, so make sure you are sat close enough together, and try to account for any hearing difficulties.

Some food for thought on listening

You are not listening to someone when:

You say you understand them when you actually do not

You have an answer for their problem before they have finished telling you what it is

You cut them off before they’ve finished speaking

You finish their sentences for them

You are dying to tell them something

You tell them about your experience, making theirs seem unimportant

You do not care about what they are saying

You are listening to someone when:

You come quietly into their private world and let them be

You really try to understand them even though they do not seem to be making sense

You grasp their point even when it’s against your own sincere convictions

You realise that the hour they took from you left you a bit tired and drained

You allow them the dignity of making their own decisions even though they might be wrong

You do not take any problem from them but allow them to deal with it in their own way

You hold back your desire to give them good advice

You give them enough room to discover for themselves what is really going on

Here are some active listening group exercises for download which you might find useful to help hone your skills:

[Exercise 1][Exercise 2][Exercise 3]